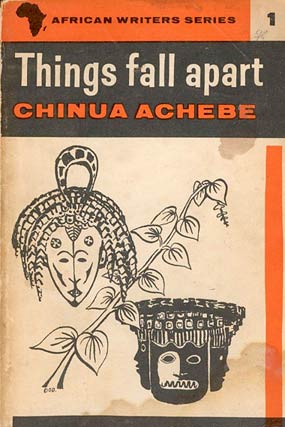

Things Fall Apart is one of the most successful books on the surface of earth and it was China Achebe’s most successful work.In this extract from his latest book, ‘THERE WAS A COUNTRY, the late writer stated that when he was writing the book he did not know whether it would be published or not.

A major objective of becoming a writer was to challenge stereotypes, myths, and the image of ourselves and our continent, and to recast them through stories – prose, poetry, essays, and books for our children. That was my overall goal.

When a number of us decided to pick up the pen and make writing a career there was no African literature as we know it today. There were of course our great oral tradition – the epics of the Malinke, the Bamana, and the Fulani – the narratives of Olaudah Equaino, works by D.A. Fagunwa and Muhammadu Bello, and novels by Pita Nwana, Amos Tutuola, and Cyprian Ekwensi.

Across the African continent, literary Aficionados could savor the works of Egyptian, Nubian, and Carthaginian antiquity, Amharic and Tigrigna writings from Ethiopia and Eritrea; and the magnificent poetry and creation myths of Somalia. There was more – the breathtakingly beautiful Swahili poetry of East and Central Africa, and the chronicles, legends, and fables of the Ashanti, Dogon, Hutu, Kalanga, Mandingo, Ndebele, Ovambo, Shona, Sotho, Swazi, Tsonga, Tswana, Tutsi, Venda, Wolof, Nhosa, and Zulu.

Olive Schreiner’s nineteenth-century classic story of an African Farm and works by Samuel Mqhayi and Thomas Mofolo, Alan Paton, Camara Laye, Mongo Beti, Peter Abrahams, and Ferdinand Oyono, all preceded our time. Still, the numbers were not sufficient.

And so I had no idea when I was writing Things Fall Apart whether it would even be accepted or published. All of this was new -there was nothing by which I could gauge how it was going to be received.

And so I had no idea when I was writing Things Fall Apart whether it would even be accepted or published. All of this was new -there was nothing by which I could gauge how it was going to be received.

Late Prof Chinua Achebe

The preparation of this life of writing, I have mentioned, came from English-system-style schools and university. I read Shakespeare, Dickens, and all the books that were read in the English public schools. They were novels and poems about English culture, and some things I didn’t know anything about. When I saw a good sentence, saw a good phrase from the Western canon, of course I was influenced by it. But the story itself – there weren’t any models. Those that were set in Africa were not particularly inspiring. If they were not saying something that was antagonistic toward us, they weren’t concerned about us.

When people talk about African culture they often mean an assortment of ancient customs and traditions. The reasons for this view are quite clear. When the first Europeans came to Africa they knew very little of the history and complexity of the people and the continent. Some of that group persuaded themselves that Africa had no culture, no religion, and no history. It was a convenient conclusion, because it opened the door for all sorts of rationalizations for the exploitation that followed. Africa was bound, sooner or later, to respond to this denigration by resisting and displaying her own accomplishments. To do this effectively her spokesmen – the writers, intellectuals, and some politicians, including Azikiwe, Senghor, Nkrumah, Nyerere, Lumumba, and Mandela – engaged Africa’s past, stepping back into what can be referred to as the “era of purity”, before the coming of Europe. We put into the books and poems what was uncovered there, and this became known as African culture.

This was a very special kind of inspiration. Some of us decided to tackle the big subjects of the day – imperialism, slavery, independence, gender, racism, etc. And some did not. One could write about roses or the air or about love for all I cared; that was fine too. As for me, however, I chose the former.

Engaging such heavy subjects while at the same time trying to help create a unique and authentic African literary tradition would mean that some of us would decide to use the colonizer’s tools, his language, altered sufficiently to bear the weight of an African creative aesthetic, infused with elements of the African literary tradition. I borrowed proverbs from our culture and history, colloquialisms and African expressive language from the ancient griots, the worldviews, perspectives, and customs from my Igbo tradition and cosmology, and the sensibilities of everyday people.

It was important to us that a body of work be developed of the highest possible quality that would oppose the negative discourse in some of the novels we encountered. By “writing back”to the West we were attempting to reshape the dialogue between the colonized and the colonizer. Our efforts, we hoped, would broaden the world’s understanding, appreciation, and conceptualization of what literature meant when including the African voice and perspective. We were clearly engaged in what Ode Ogede aptly refers to as “the politics of representation”.

This is another way of stating the fact of what I consider to be my mission in life. My kind of story telling has to add its voice to this universal story telling before we can say, “Now we’ve heard it all.”

I worry when somebody from one particular tradition stands up and says, “The novel is dead, the story is dead.” I find this to be unfair, to put it mildly. You told your own story, and now you’re announcing the novel is dead. Well, I haven’t told mine yet.

There are some who believe that the writer has no role in politics or the social upheavals of his or her day. Some of my friends say, “No, it is too rough there.

There are some who believe that the writer has no role in politics or the social upheavals of his or her day. Some of my friends say, “No, it is too rough there.

A writer has no business being where it is so rough. The writer should be on the sidelines with his notepad and pen, where he can observe with objectivity.”I believe that the African writer who steps aside can only write footnotes or a glossary when the event is over. He or she will become like the contemporary intellectual of futility in many other places, asking questions like. “Who am I? What is the meaning of my existence? Does this place belong to me or to someone else? Does my life belong to me or to some other person?”These are questions that no one can answer.

I have described earlier the practice of Mbari, the Igbo concept of “art as celebration.” Different aspects of Igbo life are integrated in this art form. Even those who are not trained artists are brought in to participate in these artistic festivals, in which the whole life of the world is depicted. Ordinary people must be brought in; a conscious effort must be made to bring the life of the village or town into this art. The Igbo culture says no condition is permanent. There is constant change in the world. Foreign visitors who had not been encountered up to that time are brought in as well, to illustrate the dynamic nature of life. The point I’m trying to make is that there is a need to bring life back into art by bringing art into life, so that the two can hold a conversation.

We established the Society of Nigerian Authors (SONA) in the mid-1960s as an attempt to put our writers in a firm and dynamic frame. It was sort of a trade union. We thought it would keep our members safe and protect other artists as well. We hoped that our existence would create an environment in Nigeria where freedom of creative expression was not only possible but protected. We sought ultimately through our art to create for Nigeria an environment of good order and civilization – a daunting task that needed to be tackled in a country engulfed in crisis.

It is important to state that words have the power to hurt, even to denigrate and oppress others. Before I am accused of prescribing a way in which a writer should write, let me say that I do think that decency and civilization would insist that the writer take sides with the powerless. Clearly there is no moral obligation to write in any particular way. But there is a moral obligation, I think, not to ally oneself with power against the powerless. An artist, in my definition of the word, would not ,be someone who takes sides with the emperor against his powerless subjects. If one didn’t realize the world was complex, vast, and diverse, one would write as if the world were one little country, and this would make us poor, and we would have impoverished the novel and our stories.

The reality of today, different as it is from the reality of my society one hundred years ago, is and can be important if we have the energy and the inclination to challenge it, to go out and engage with its peculiarities, with the things that we do not understand. The real danger is the tendency to retreat into the obvious, the tendency to be frightened by the richness of the world and to clutch what we always have understood. The writer is often faced with two choices – turn away from the reality of life’s intimidating complexity or conquer its mystery by battling with it. The writer who chooses the former soon runs out of energy and produces elegantly tired fiction.

One thing that I find a little worrying, though, is the suggestion that perhaps what was done in the 1960s, when African literature suddenly came into its own, was not as revolutionary as we make it out to be. That African literature without a concerted effort on the part of the writers of that era would still have found its voice. You find the same kind of cynicism among young African Americans who occasionally dismiss the contributions of the civil rights activists of that same period. Many of these same critics clearly did not know (or maybe do not want to be told) what Africa was like in the 1940s, back when there was no significant literature at all.

There are people who do not realize that it was a different world than the world of today, one which is far more open. This openness and the opportunities that abound for a young intellectual setting out to carve a writing career for him or herself are in fact partly a result of the work of that literature, the struggles of that era. So even though nobody is asking the new writer or intellectual to repeat the stories, the literary agenda or struggles of yesteryear, it is very important for them to be aware of what our literature achieved, what it has done for us, so that we can move forward.

As I write this I am aware that there are people, many friends of mine, who feel that there are too many cultures around. In fact, I heard someone say that they think some of these cultures should be put down, that there are just too many. We did not make the world, so there is no reason we should be quarreling with the number of cultures there are. If any group decides on its own that its culture is not worth talking about, it can stop talking about it. But I don’t think anybody can suggest to another person, Please drop your culture; let’s use mine. That’s the height of arrogance and the boast of imperialism. I think cultures know how to fight their battles; cultures know how to struggle. It is up to the owners of any particular culture to ensure it survives, or if they don’t want it to survive, they should act accordingly, but I am not going to recommend that.

My position, therefore, is that we must hear all the stories. That would be the first thing. And by hearing all the stories we will find points of contact and communication, and the world story, the Great Story, will have a chance to develop. That’s the only precaution I would suggest – that we not rush into announcing the arrival of this international, this great world story, based simply on our knowledge of one or a few traditions. For instance, in America there is really very little knowledge of the literature of the rest of the world. Of the literature of Latin America, yes. But that’s not all that different in inspiration from that of America, or of Europe. One must go further. You don’t even have to go too far in terms of geography – you can start with the Native Americans and listen to their poetry.

Most writers who are beginners, if they are honest with themselves, will admit that they are praying for a readership as they begin to write. But it should be the quality of the craft, not the audience, that should be the greatest motivating factor. For me, at least, I can declare that when I wrote Things Fall Apart I couldn’t have told anyone the day before it was accepted for publication that anybody was going to read it. There was no guarantee; nobody ever said to me, ‘Go and write this, we will publish it, and we will read it;’ it was just there. But my brother-in-law, who was not a particularly voracious reader, told me that he read the novel through the night and it gave him a terrible headache the next morning. And I took that as an encouraging endorsement!

The triumph of the written word is often attained when the writer achieves union and trust with the reader, who then becomes ready to be drawn deep into unfamiliar territory, walking in borrowed literary shoes so to speak, toward a deeper understanding of self or society, or of foreign peoples, cultures, and situations.

No comments:

Post a Comment